A Southside Chicago native, graduate of both Northeastern Illinois University and the University of Toronto, and head of the Ray Charles Program at Dillard University, Zella Palmer is an individual who wears many hats. Her top priority is creating a safe, community-based space for program participants to learn through experience.

Palmer grew up in a family of activists who aided in the cultivation of her work ethic and care for the community, she said. Originally, she planned to go to culinary school, but instead decided to pursue a degree in museum studies.

Her reasoning? She was always interested in museums, and rather than being bound to the kitchen, Palmer was more interested in the “intersectionality between food and culture,” she said.

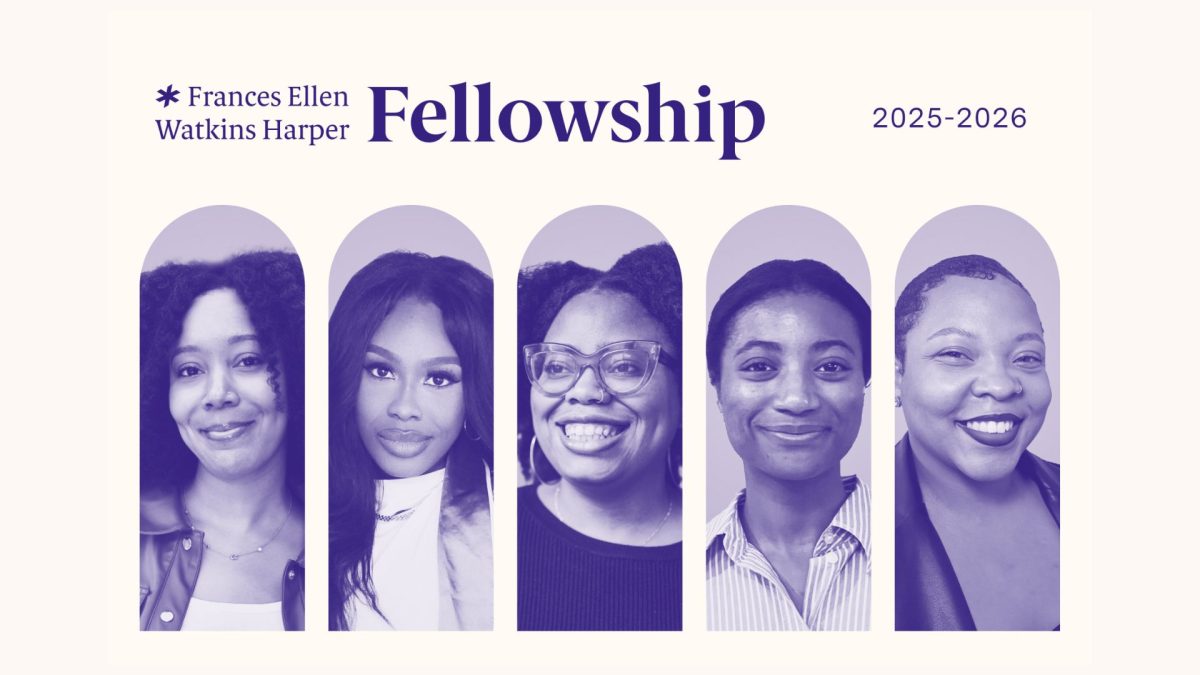

As head of the Ray Charles Program, Palmer juggles many tasks; she is a cook, a gardener, a grant writer, a counselor for students, and an “extended auntie,” she said. In addition, she assumes the responsibility of directing staff, interns, and fellows from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, as well as managing the program’s social media account. Outside of the program, she is also an advocate for local chefs, farmers, and fishermen.

Palmer describes the program as a place “where culture meets education.” The team works hard to preserve black material culture, which refers to tangible objects or expressions of culture, such as food, music, and art, in a time when these rich aspects of culture face significant challenges. Those within the program also work to honor the late vision of Ray Charles, a child of two sharecropper parents who felt the younger generation of African Americans strayed from their roots in cooking and agriculture.

The program’s food pantry is also their biggest success, according to Dr. Palmer. She said its creation was inspired by her aunt and her Mississippi grandmother’s pantries, which she always remembered being full..

“Having this pantry with real food means a lot to me,” said Palmer. The food pantry includes authentically-grown food and other handmade items. It’s a successful attempt by Palmer, in partnership with the university, to create a sustainable source of good, clean, real food for students.

In 2014, Palmer recalls only having a memo from Ray Charles when she started. Now, the program has grown exponentially thanks to the foundation she, other staff members and students have created.

To Palmer, the program is not simply about the food or cooking. It is supposed to be a source of “life, music, food, and good times,” she said. She said students participating in the program can be themselves and thrive, considering the stress they face from everyday life and school. For her students within the program, Palmer said she hopes that after participating, they will “see the world” and understand that nothing done is ever wasted. For her, the most meaningful and powerful opportunities arise from interacting, eating, and building community with others.

According to Palmer, her students have done just that. Several Dillard Alumni who have worked in the program have gone on to become what Palmer would describe as “global citizens.”Brianna Smith, a student who was president of the Slow Food Chapter, went on to travel the world, studying in Chile and Mexico. She was even accepted to the University of Toronto, Palmer’s alma mater.

Another student, Jamir Morris, who Palmer said was initially a bad cook, interned with a chef, and moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, to create his own catering business.

Lastly, Chip Knadake, a film major who remained active in the program, became a Mardi Gras Indian queen, dance and music historian, vegan cook, and filmed her first documentary.

The program has not only enabled students to achieve higher degrees of success post-grad by giving them a space to interact with new culture and people, but it has also given them lifelong memories they would not trade, said Palmer. She distinctly recalls memories like a student who struggled with migraines finally experiencing relief when eating actual unprocessed food in Italy, or another student who tried a real tomato for the first time in Italy while with the Ray Charles Program.

Palmer said she loves being able to aid in the students’ experiential, hands-on learning gained from creating their own food. She also enjoys collaborating with faculty and administration to create this experience for the students. These aspects are the most rewarding part of the whole job for her. Seeing the response from the school administration and international chefs lets her know her work with the program since 2014 has made an impact, she said.

Palmer’s main source of inspiration to continue her work is the students. She has seen them remain intelligent, brilliant, optimistic, and exceptionally human despite the current, shifting state of the world, she said.

When she is not working feverishly in the Ray Charles program, she adores dancing.

“Give me some live music and I am whining my hips, ” she exclaimed. Palmer enjoys reading, watching retro films, and frequenting museums as well, she said.

Palmer is a vibrant soul dedicated to her work of introducing students to the possibility of intersectionality between food and other aspects of life. Considering the current challenges to education, Palmer prides herself on “reclaiming and decolonizing education” through hands-on teaching and fun experiences that reconnect students to their roots in agriculture, a lost skill, she said.

For more specific details regarding the program, visit the section on the program on Dillard University’s website or the Instagram page: @dillard_raycharles